Mon - Sat 9:00 - 17:30

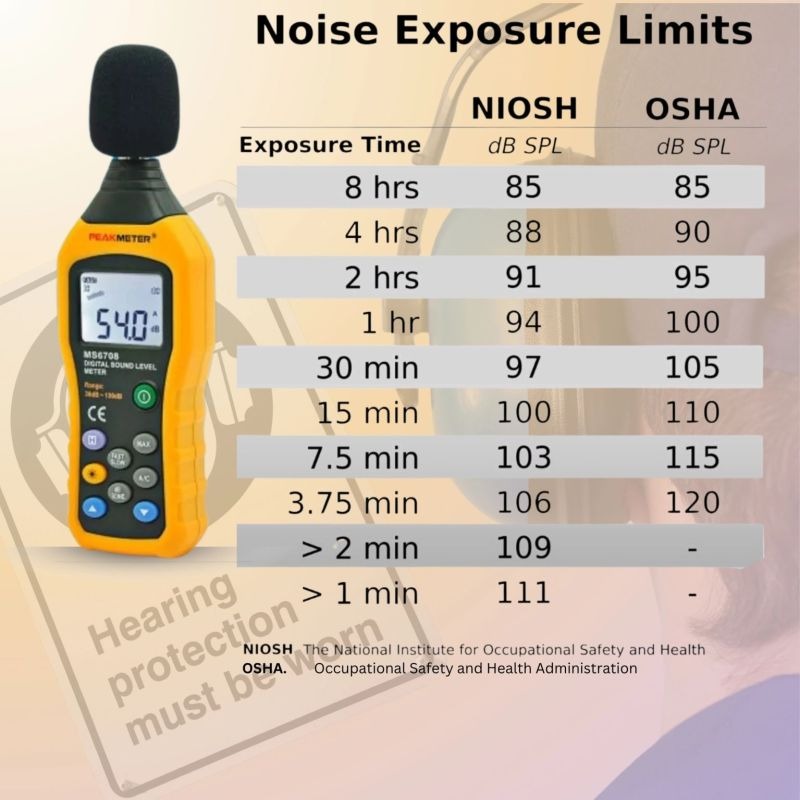

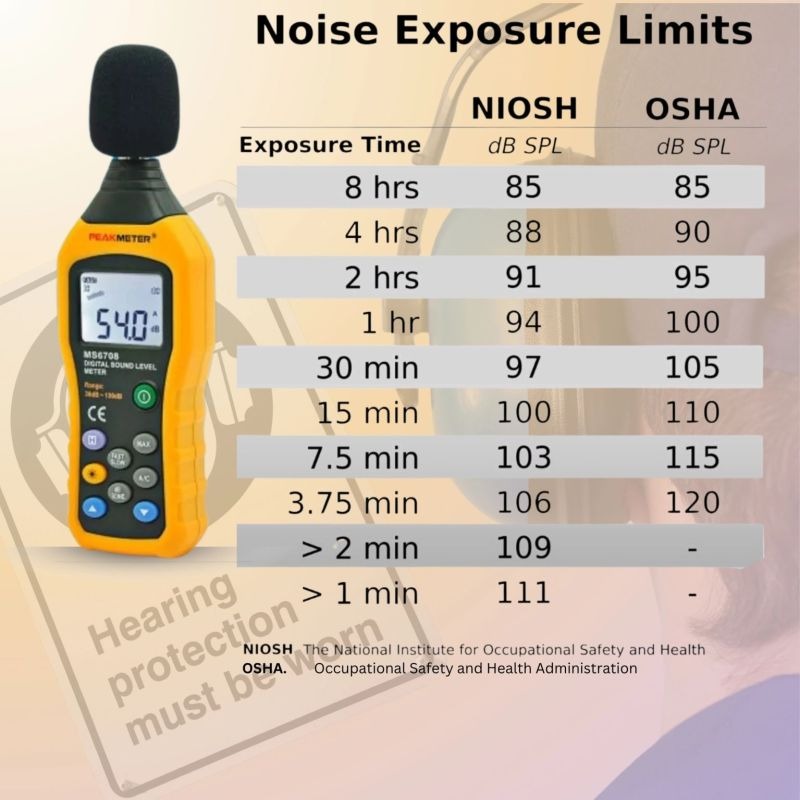

Noise is an invisible but pervasive hazard in many modern environments, from bustling factory floors to busy city streets. Unlike other industrial injuries, Noise-Induced Hearing Loss (NIHL) is painless, gradual, and cumulative. By the time it's noticed, the damage is permanent. The image provided highlights the critical safety standards set by two major U.S. organizations—NIOSH (The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) and OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration). This article explores these limits, the severe consequences of exceeding them, and the global and Indian regulations designed to protect our hearing.

Noise exposure is measured by two factors: intensity (loudness) in decibels (dB) and duration (time). The core principle of noise safety is a "dose" relationship: the louder the noise, the less time you can be safely exposed before damage occurs.

The chart in the image clearly illustrates a critical difference in safety philosophies:

NIOSH (The Scientific Recommendation): NIOSH recommends a limit of 85 dB for an 8-hour workday. It uses a 3-dB exchange rate. This is the "equal-energy rule," which states that for every 3-dB increase in noise, the sound energy doubles, and the permissible exposure time should be halved. For example, at 88 dB, the safe time is only 4 hours; at 91 dB, it's 2 hours.

OSHA (The Legal Standard): OSHA's standard, which is legally enforceable in the U.S., is more lenient. While it requires a "Hearing Conservation Program" to start at 85 dB (the "action level"), its permissible exposure limit (PEL) is 90 dB for 8 hours. It uses a 5-dB exchange rate, meaning exposure time is halved for every 5-dB increase (e.g., 95 dB for 4 hours, 100 dB for 2 hours).

As the chart shows, NIOSH's recommendations are significantly more protective. For example, at 100 dB (the sound of a chainsaw), NIOSH recommends exposure of 15 minutes, while OSHA permits 1 hour.

When loud noise enters the ear, it causes violent vibrations that damage the delicate hair cells (stereocilia) in the inner ear (cochlea). These cells are responsible for converting sound vibrations into electrical signals for the brain.

This damage is irreversible and leads to several consequences:

Permanent Hearing Loss (PTS): This is the most common result. The hair cells die and do not grow back, leading to a permanent loss of hearing, especially at higher frequencies.

Tinnitus: A persistent ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ears, even in complete silence. It can be a debilitating and constant source of stress.

Temporary Threshold Shift (TTS): A temporary muffling or dullness of hearing, often experienced after a loud event like a concert. While hearing recovers, repeated TTS can lead to permanent damage.

Systemic (Whole-Body) Impacts: Noise acts as a physical stressor on the body. Chronic exposure can lead to increased heart rate, high blood pressure (hypertension), sleep disturbances, anxiety, and reduced cognitive performance.

These consequences directly influence decisions at both the organizational and personal levels. For a company, exceeding these limits triggers legal requirements for costly engineering controls, mandatory audiometric testing, and providing hearing protection. For an individual, understanding these risks should influence decisions to wear hearing protection when using power tools, attending loud events, or even mowing the lawn.

To monitor for hearing damage, workplaces use pure-tone audiometry. This is a hearing test that determines the quietest sound a person can hear at various pitches (frequencies).

Frequencies Checked

An occupational audiogram typically tests a range of frequencies, but the most important for monitoring noise-induced hearing loss are:

500 Hz

1,000 Hz

2,000 Hz

3,000 Hz

4,000 Hz

6,000 Hz

How to Interpret the Results

The results are plotted on a graph called an audiogram. The vertical axis shows loudness in decibels (dB HL), and the horizontal axis shows frequency in Hertz (Hz).

Normal Hearing: A person with normal hearing can detect all frequencies at 25 dB or quieter.

The "Noise Notch": The classic, tell-tale sign of noise-induced hearing loss is a distinct "notch" or dip in hearing ability on the audiogram, which is almost always centered around the 4,000 Hz frequency.

Standard Threshold Shift (STS): This is the most critical metric for workplace safety programs. OSHA defines an STS as an average worsening of hearing of 10 dB or more at 2,000, 3,000, and 4,000 Hz in either ear, compared to the employee's initial baseline audiogram. An STS is a red flag that indicates the worker's hearing is being damaged and immediate intervention is required.

Noise exposure is regulated by law in most countries to protect workers.

Global Standards:

United States (OSHA/NIOSH): As discussed, OSHA sets the legal PEL at 90 dBA (with an 85 dBA action level), while NIOSH recommends a stricter 85 dBA limit.

European Union (EU): The EU directive (2003/10/EC) is even more stringent, setting a lower action level of 80 dBA and an exposure limit of 87 dBA.

Regulations in India:

In India, occupational noise is primarily regulated by The Factories Act, 1948 (specifically, the Model Rules for various states).

The permissible exposure limit (PEL) for most Indian factories is 90 dBA for an 8-hour workday.

The Act follows the 5-dB exchange rate, similar to OSHA. This means the limit is 95 dBA for 4 hours, 100 dBA for 2 hours, and so on.

The law mandates that if noise levels exceed this 90 dBA limit, the employer must implement a hearing conservation program, which includes noise surveys, engineering controls, and periodical audiometric testing for all exposed workers.

The most effective way to prevent hearing injuries is not just to hand out earplugs. Best-in-class safety programs follow the Hierarchy of Controls, which prioritizes solutions from most to least effective.

Elimination / Substitution (Most Effective): The best solution is to get rid of the hazard.

Eliminate: Remove the noisy process entirely.

Substitute: Replace a dangerously loud machine with a newer, quieter model. Implementing a "Buy Quiet" policy when purchasing new equipment is a benchmark practice.

Engineering Controls: If the noise source can't be eliminated, isolate it.

Build sound-proof enclosures or barriers around machinery.

Install mufflers or silencers on exhausts.

Use sound-absorbing materials on walls and ceilings.

Administrative Controls: Change the way people work to reduce their exposure.

Rotate workers: Limit the time any single worker spends in a high-noise area.

Schedule: Run noisy operations during shifts when fewer people are present.

Create "quiet zones" for breaks.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) (Least Effective): This is the last line of defense, used only when the above controls cannot reduce noise to safe levels.

This includes earplugs and earmuffs.

PPE is highly dependent on a proper fit, consistent use, and good maintenance. If an earplug is not inserted correctly, its protective value drops dramatically.

By combining these steps into a comprehensive Hearing Conservation Program—which includes noise monitoring, audiometric testing, training, and providing all levels of control—hearing-related injuries can be entirely eliminated.