Mon - Sat 9:00 - 17:30

This briefing dissects the phenomenon of decision fatigue by analyzing its neural mechanisms, observable behavioral markers, and cascading impacts on emergency management systems. It further outlines evidence-based tactical countermeasures, from cognitive offloading tools to temporal restructuring, and details rigorous recovery protocols designed to restore the cognitive capabilities of command personnel. The analysis synthesizes research from neuroimaging, organizational psychology, and established emergency management doctrine to present a holistic framework for cognitive resource management in crisis.

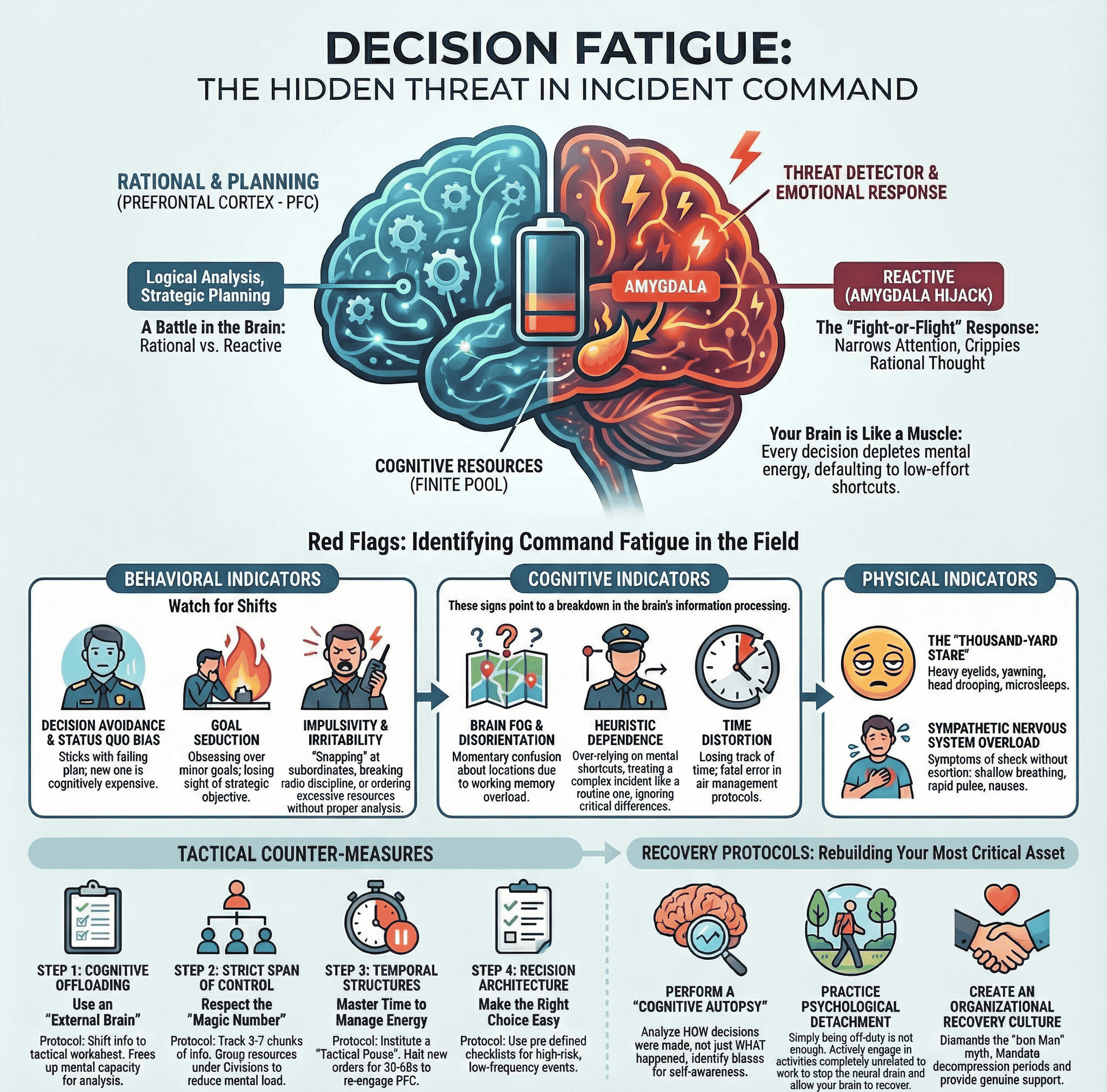

Decision fatigue is a complex alteration in brain function that degrades the ability to value effort, process risk, and inhibit impulses. This erosion is rooted in the architecture of the brain's executive control systems.

Effective incident command depends on Executive Function (EF), a suite of high-level cognitive processes based in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) is central to this, managing working memory, logical analysis, and top-down behavioral regulation.[1] In optimal conditions, the PFC exerts inhibitory control over primitive, emotion-driven structures like the Amygdala and Ventral Striatum.

Decision fatigue disrupts this hierarchy. As fatigue accumulates, the brain must recruit additional neural resources to maintain performance, a state of inefficient processing.[2] Eventually, this compensatory mechanism fails, weakening the PFC's top-down control and causing the brain to default to "bottom-up" processing driven by the amygdala.

The Strength Model of Self-Control posits that humans have a limited reservoir of regulatory capacity, much like a muscle that tires with use.[5] Each decision depletes this resource. As "ego depletion" sets in, the brain enters a conservation mode, avoiding the metabolically costly DLPFC and defaulting to low-energy pathways like heuristics and biases.[5]

Fatigue alters the brain's computation of value, demanding a higher reward for a given unit of cognitive effort.[6] In a crisis, the IC's brain subconsciously determines that the cognitive "cost" of re-evaluating a failing strategy is too high. This neurobiological predisposition leads the IC to exploit known, familiar strategies rather than explore new, potentially more effective options.[7] This prioritizes metabolic efficiency over tactical optimization, effectively taking the future-simulating DLPFC offline.

The following table outlines the key neural structures involved in command and how decision fatigue impairs their function.

|

Neural Component |

Function in Command |

Effect of Decision Fatigue |

|

Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) |

Logical analysis, working memory, strategic planning. |

Reduced activity; failure of inhibition; impaired trade-off analysis.[2] |

|

Amygdala |

Threat detection, emotional response (Fight/Flight). |

Hyperactivity; "Hijacks" control from PFC; induces tunnel vision.[3] |

|

Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) |

Error detection, conflict monitoring, effort allocation. |

Impaired ability to detect errors in judgment or conflicting data.[9] |

|

Ventral Striatum |

Reward processing, motivation. |

Shifts preference toward immediate gratification and low-effort solutions.[7] |

|

Right Insula |

Interoceptive awareness, effort perception. |

Increased activity correlates with the subjective feeling of mental exhaustion.[2] |

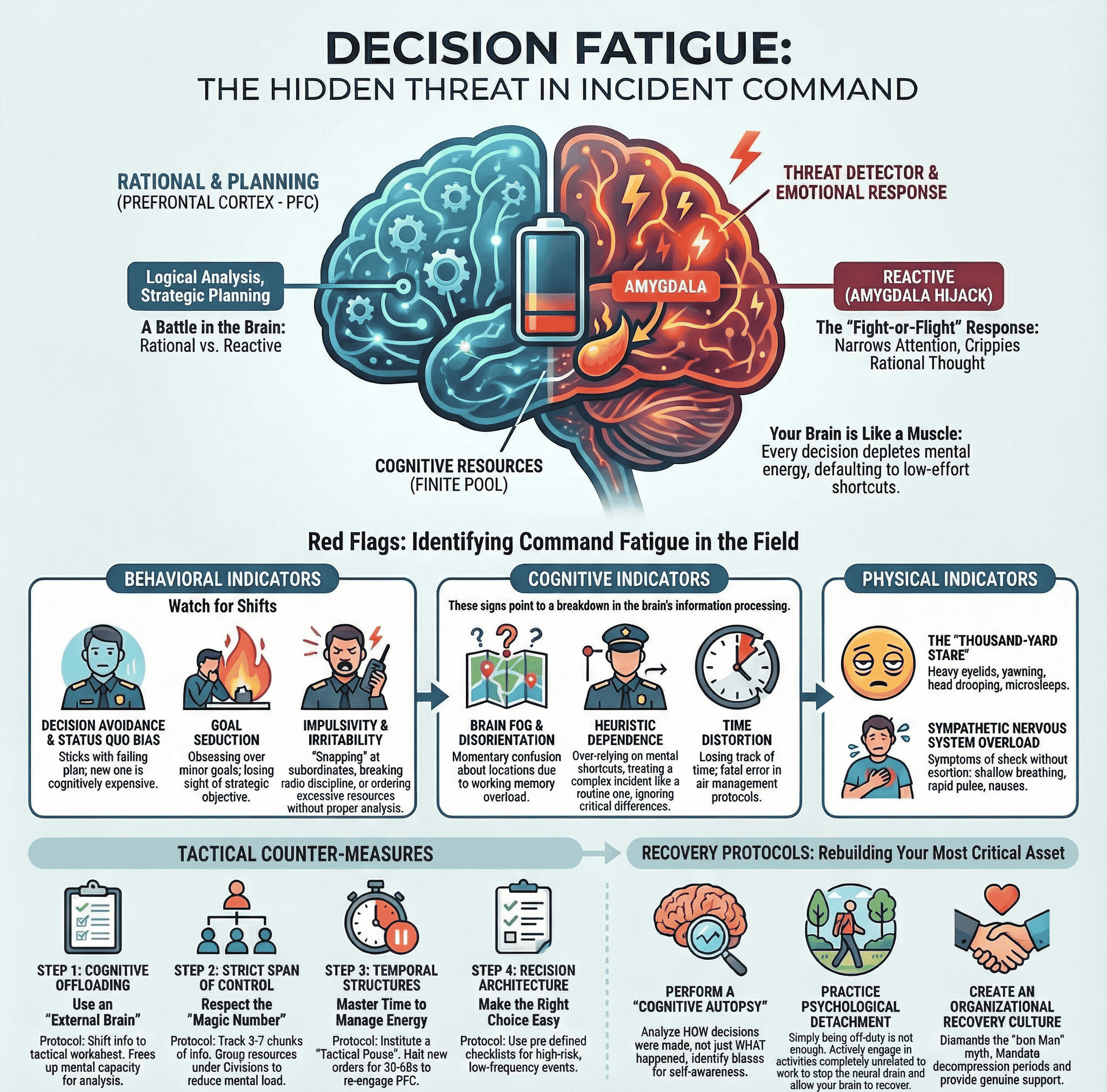

The onset of decision fatigue is often gradual and masked by adrenaline, making it difficult to detect until a critical error occurs. Incident Safety Officers (ISOs) and commanders must be trained to recognize its behavioral, cognitive, and physical markers.

ISOs should actively monitor the command post for the following red flags:

|

Category |

Red Flag Indicator |

Mechanism/Implication |

Source Evidence |

|

Communication |

Failure to communicate important information; silence on the radio; snapping at dispatchers. |

Breakdown of Broca’s area function; reduced verbal fluency; irritability due to inhibition failure. |

[14] |

|

Command Presence |

"Resigned" attitude ("we can't make a difference"); withdrawal from the command board; lack of clear directives. |

Learned helplessness; dopamine depletion impacting motivation (ventral striatum). |

[14] |

|

Decision Quality |

Making mistakes on well-practiced tasks; inability to anticipate events (reactive vs. proactive). |

Executive function failure; inability to simulate future states (prospective memory failure). |

[14] |

|

Emotional State |

Irritability with staff; heightened emotional sensitivity; dark humor inappropriate to the moment. |

Amygdala hijack; loss of emotional regulation. |

[13] |

|

Physical Appearance |

Head drooping; blank stare; pale/moist skin; obvious exhaustion; yawning. |

Sleep pressure; autonomic dysregulation. |

[14] |

|

Risk Tolerance |

"Invulnerable" or "Macho" attitudes; impulsive risk-taking; disregard for established safety rules. |

Hazardous attitudes; impairment of risk assessment circuitry. |

[12] |

Decision fatigue in an IC propagates outward, creating cascading failures throughout the response network. The degradation of this central node disrupts the entire system.

Decision fatigue introduces a single point of failure that emergency plans rarely account for.[23]

When subordinates perceive that the IC is compromised, the chain of command degrades.

These strategies are designed to manage cognitive load and extend the IC's operational endurance.

This is the practice of shifting information processing from limited internal working memory to external tools.[26]

The ICS standard of a 1:3 to 1:7 span of control is a neurobiological necessity. The brain can only hold 3 to 7 "chunks" of information in working memory at once, a capacity that shrinks under stress.[34] Creating Branches, Divisions, and Groups is the tactical application of "chunking," reducing multiple data points into a single manageable unit in the IC's mind.[37]

|

Counter-Measure |

Mechanism of Action |

Implementation Protocol |

|

Tactical Worksheets |

Cognitive Offloading; frees Working Memory. |

Mandatory use for every incident > 2 units. Use standardized, pre-printed boards.[29] |

|

Strict Span of Control |

Reduces Intrinsic Load via "Chunking." |

Never exceed 1:5 ratio. Establish Divisions/Groups immediately upon saturation.[34] |

|

Tactical Pause |

Interrupter for Amygdala Hijack; re-engages PFC. |

"Look, Listen, Think" loop every 10-20 mins or at strategy shifts.[40] |

|

Decision Architecture |

Reduces decision fatigue by pre-deciding options. |

Use "Go/No-Go" checklists for high-risk events (Mayday, Evacuation).[30] |

|

Glucose/Hydration |

Physiological fuel for neural activity. |

Stable blood glucose maintenance; avoid sugar spikes; hydration mandated by ISO.[26] |

Recovery from the neurochemical toll of a high-stakes incident requires a structured approach to rebuild cognitive assets and prevent burnout.

This metacognitive tool focuses not on what happened, but on how decisions were made.[44] The IC should first perform this process alone, writing down all thoughts, feelings, and pressures experienced during the event. The goal is to identify cognitive biases (e.g., anchoring bias) that were used.[46] These findings can then be discussed in a safe peer-review setting to normalize cognitive fallibility and build neural "warning systems" for future events.[45]

The organization must treat recovery as a logistical operation. This includes:

Decision fatigue is an occupational hazard for Incident Commanders, as tangible and dangerous as any physical threat. The erosion of cognitive faculties begins with neurochemical shifts in the Prefrontal Cortex, manifests as behavioral dysfunction, and can culminate in the cascading failure of the entire response system.

Modern emergency services must move beyond the myth of the infallible commander and adopt a doctrine of Cognitive Resource Management. By integrating the neuroscience of erosion into training, deploying tactical countermeasures like cognitive offloading and strict span of control, and practicing rigorous recovery protocols, we protect not just the commander, but the community they serve. The safety of the public ultimately rests on the clarity of command decisions. In this context, the "tactical pause" is not hesitation; it is the hallmark of a professional mind preserving its most critical weapon: the ability to think.