Mon - Sat 9:00 - 17:30

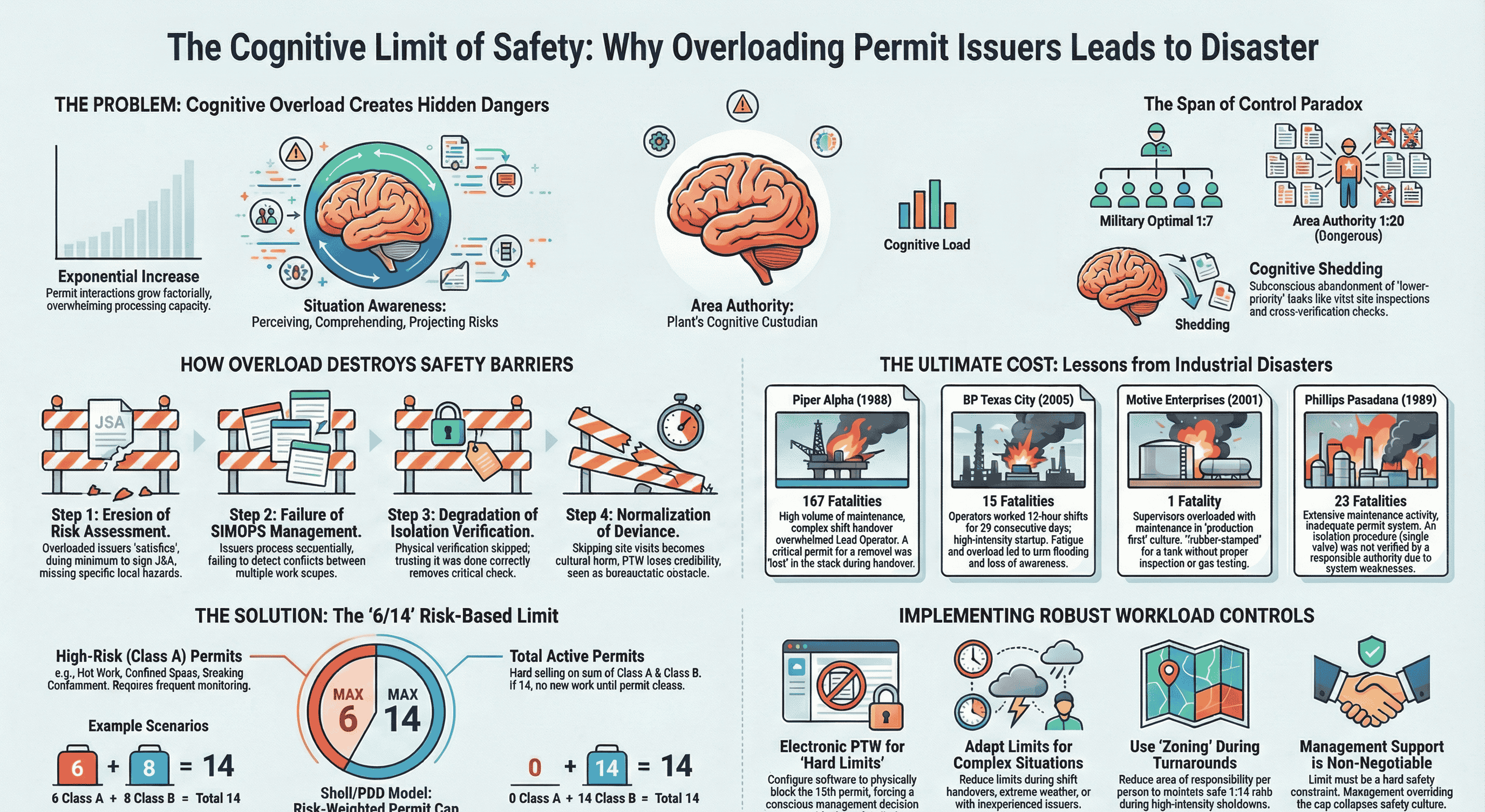

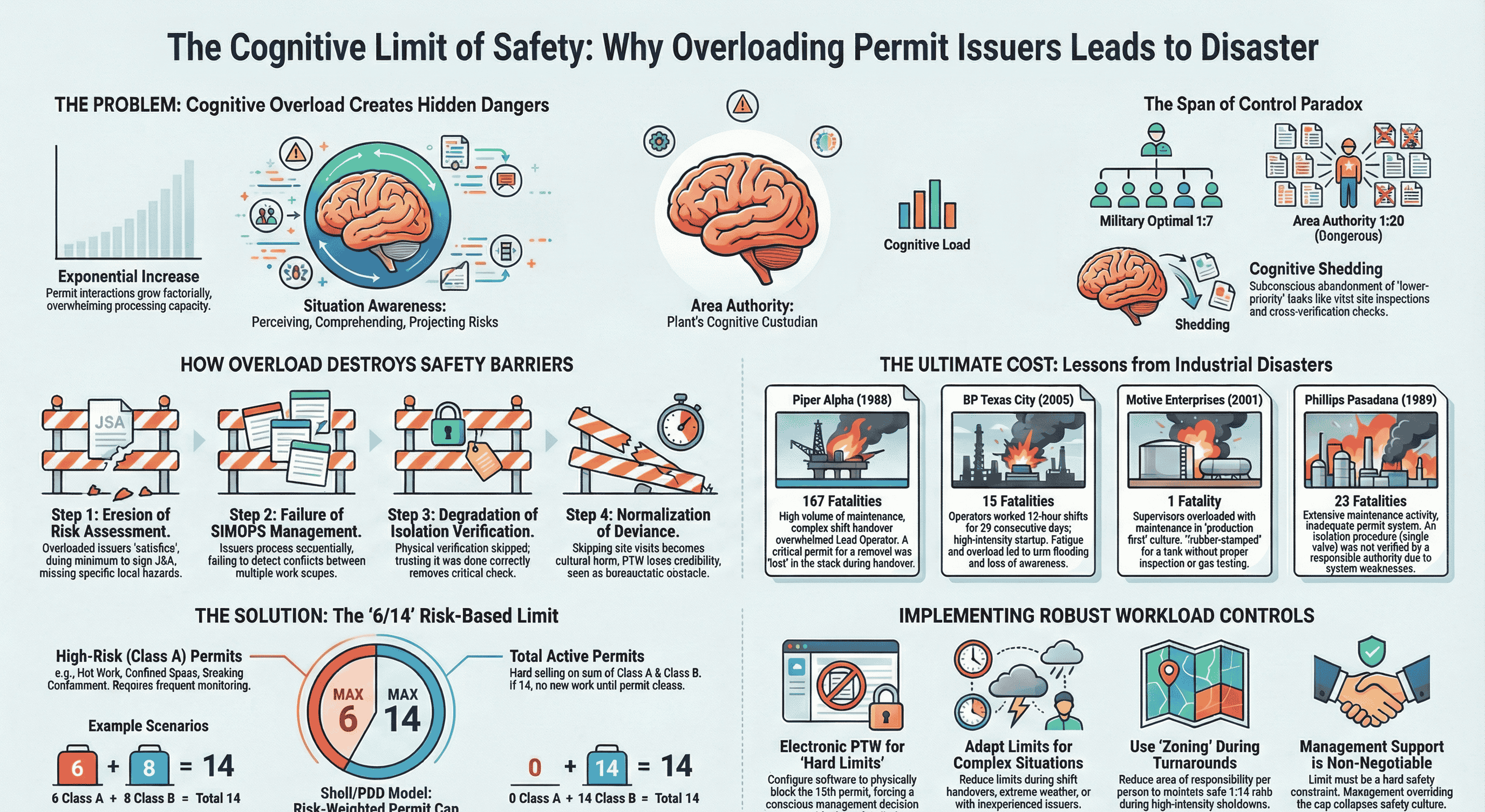

Even the most skilled professionals—pilots, surgeons, engineers—have a cognitive limit. In our daily lives, exceeding this limit might mean forgetting an appointment or making a mistake on a spreadsheet. But in high-risk industries like oil and gas, exceeding this limit isn't about dropping a ball—it's about creating a path to catastrophe. A simple piece of paper, the work permit, is the final barrier standing between a safe job and a disaster. This document explores the tragic history that taught us why managing these permits is a life-or-death responsibility, and why the most important safety rule is knowing when to say "stop."

1. The Most Important Job: Understanding the "Area Authority"

In any hazardous work environment, one person is designated as the Area Authority (or Permit Issuer). Think of them as the "brain" of the worksite. Their job is to maintain a complete, real-time mental map of every single activity happening in their area. They are the single point of accountability for the safety of the asset and everyone working on it.

For every single work permit they approve, the Area Authority must continuously track several critical variables:

As the number of active permits increases, the number of potential conflicts between them doesn't just double or triple—it expands factorially, making it impossible for the human brain to track every interaction. This is the concept of Cognitive Overload. It is not a matter of willpower; the human brain has a finite processing speed. It becomes physically impossible for one person to track every potential interaction, identify every risk, and keep everyone safe.

When the brain is overloaded, it begins to shed tasks to cope, leading to critical and often fatal mistakes.

When an Area Authority is overwhelmed, their brain subconsciously looks for ways to reduce the mental strain. This coping mechanism leads to dangerous shortcuts that systematically break down the safety barriers a permit is designed to create.

These shortcuts are not theoretical. They are the direct precursors to real-world, catastrophic events that have shaped modern industrial safety.

3.1. Piper Alpha (1988): The Lost Permit

On the Piper Alpha offshore platform, the Lead Operator was managing a complex shift handover with a high volume of maintenance work. Buried in the stack of paperwork was a critical permit for a Pressure Safety Valve (PSV) that had been removed for service, meaning a major pipe was not protected from overpressure. During the hectic handover, this permit was effectively "lost." The oncoming shift, completely unaware that the safety valve was missing, started a condensate pump connected to that same pipe. The resulting overpressure and leak led to a series of massive explosions that destroyed the platform and killed 167 people. The high workload directly caused the failure to cross-reference the Pump Start permit with the PSV Removal permit.

3.2. BP Texas City (2005): The Fatigued Mind

At the BP Texas City refinery, operators were working under extreme conditions, with many on 12-hour shifts for 29 consecutive days. During a complex and high-intensity unit startup, the board operator was cognitively overloaded and severely fatigued. This led to what investigators called a "loss of situational awareness," made worse by an overwhelming flood of alarms they could no longer interpret. Operators dangerously overfilled a distillation tower with flammable hydrocarbons, ignored multiple warnings, and vented the excess liquid to the atmosphere. The resulting vapor cloud ignited, causing a massive explosion that killed 15 people and injured more than 180 others. The investigation cited fatigue and an unmanageable span of control as root causes of the disaster.

These stories, though different in their details, reveal an underlying pattern of failure rooted in human limitations.

These cases demonstrate a recurring pattern, a predictable and repeatable equation for disaster: High Workload + Fatigue = Skipped Verification = Latent Hazard Activation. The core elements are a high-pressure environment that overloads the people in charge, leading to the breakdown of established safety procedures.

|

Incident |

The Human Factor |

The Consequence |

|

Piper Alpha |

High workload during shift handover. |

A critical safety permit was "lost," leading to conflicting work being approved. 167 dead. |

|

BP Texas City |

Extreme worker fatigue and cognitive overload during a high-intensity startup. |

Operators lost situational awareness, leading to a procedural failure. 15 dead. |

This pattern is explained by sociologist Diane Vaughan's concept of the "Normalization of Deviance." When people are constantly overloaded, dangerous shortcuts—like skipping a site visit or "rubber-stamping" paperwork—become the normal, accepted way to get the job done. The exception becomes the rule. An entire culture slowly drifts toward danger, becoming blind to the risks it is taking until it is too late. A disaster becomes not a matter of if, but when.

The hard-won lessons from these tragedies have led directly to the modern safety rules designed to prevent them from ever happening again.

5. Conclusion: A Rule to Live By

The central lesson forged from these tragedies is simple and absolute: limiting the number of active work permits an individual can manage is not a bureaucratic suggestion, but a fundamental safety barrier. It is a system engineered to "protect the protector," ensuring the very person in charge of safety has the mental bandwidth to do their job without being overwhelmed.

Industry has translated these painful lessons into clear, life-saving rules. One of the most common is the "6/14 Rule," which dictates that a single Area Authority can manage a maximum of 14 total active permits, with no more than 6 of those being high-risk activities like working in a confined space. This isn't an arbitrary number; it's a hard limit based on the science of human cognition and the forensic history of disaster.

Respecting these limits is about more than just following a procedure. It is how we honor the memory of the 167 people lost on Piper Alpha and the 15 lost at Texas City. The cost of limiting permits is measured in minutes of maintenance delay; the cost of ignoring the limit is measured in lives and assets lost.