Mon - Sat 9:00 - 17:30

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

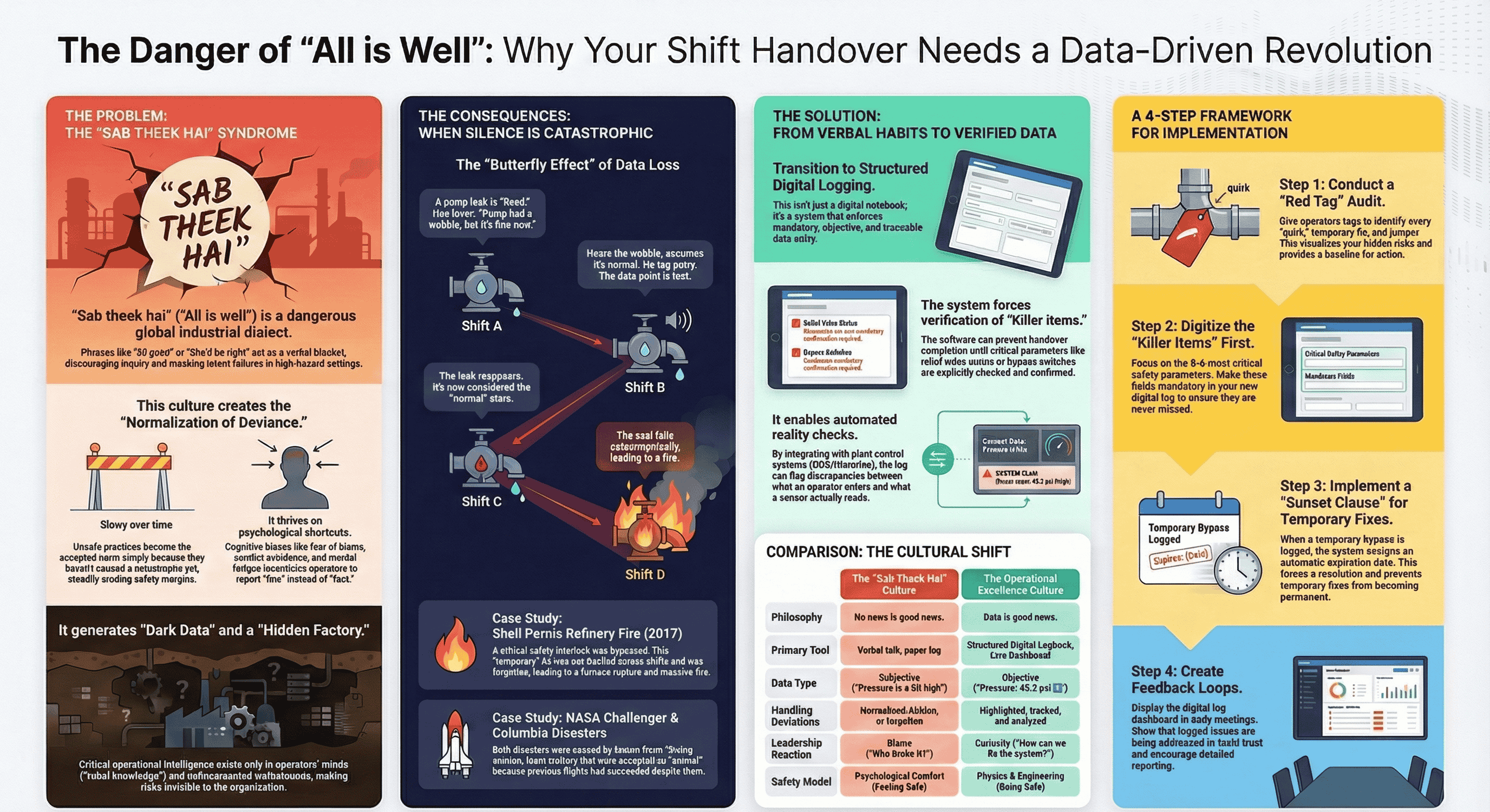

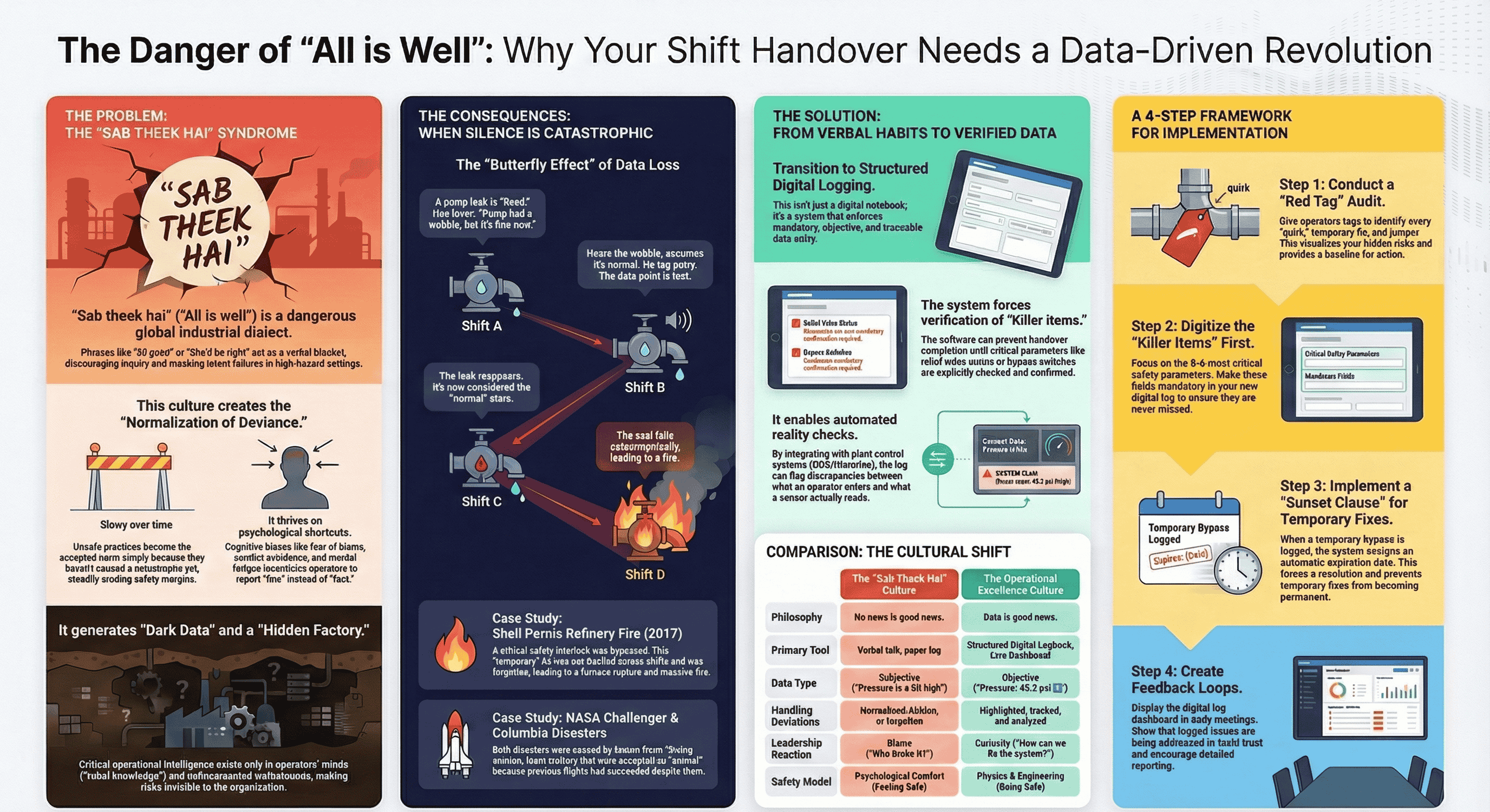

The phrase "Sab Theek Hai" (Hindi for "All is well") is more than a simple statement; it is a universal industrial dialect spoken in control rooms worldwide. Whether expressed as "All good" in the US or "She'll be right" in Australia, its function is the same: to provide a quick, reassuring summary of a plant's status. While socially convenient, this mindset is structurally dangerous in a high-hazard environment.

The core danger of this mindset is that it shifts the incoming operator from a state of "alert investigation" to "passive acceptance." This creates a dangerous disconnect between the plant's Physical Reality (the actual pressures, temperatures, and equipment states) and the operators' Perceived Reality (the belief that everything is stable).

This casual assurance is the bedrock of a phenomenon known as the Normalization of Deviance. This is a gradual process where unsafe practices or deviations from technical standards become the accepted norm simply because they have not yet resulted in a catastrophe. The practical mechanism that fuels this normalization is often a "Chalta Hai" ("It will do") attitude. For example, an operator might use a "temporary" clamp on a minor leak instead of following a lengthy repair procedure because it's easier and keeps production running. When the clamp holds, the deviation is smoothed over by a "Sab Theek Hai" handover, and the unsafe practice begins its journey to becoming the new standard.

This culture is driven by powerful psychological factors that encourage operators to prefer comfortable narratives over uncomfortable data. The two most important drivers are:

This dangerous culture of verbal reassurance and normalized deviation set the stage for the specific sequence of failures that occurred at the Shell Pernis refinery.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In August 2017, a major fire erupted at the Shell Pernis refinery in Rotterdam. The immediate cause was the rupture of a furnace tube. The process flow through the tube had stopped, but the furnace's burners continued to fire. This caused the stagnant hydrocarbons inside the tube to overheat, pressurize, and ultimately burst, releasing over 100 metric tons of flammable liquid that quickly ignited.

The chain of events leading to this disaster reveals a classic failure of both technical and human systems:

This step-by-step breakdown shows how the disaster was not an unforeseeable accident, but the logical conclusion of a series of human errors rooted in poor communication.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Shell Pernis fire was not just a technical failure of a furnace; it was the predictable outcome of a communication and cultural failure. The casual acceptance of a bypassed safety system, combined with an informal handover, created the exact conditions necessary for the disaster.

The table below connects the theoretical concepts of a "Sab Theek Hai" culture to the practical events of the incident.

|

Concept |

Application at Shell Pernis |

|

Normalization of Deviance |

The "temporary" bypass of the safety interlock became the new, accepted baseline for operations, as it hadn't caused an immediate accident on previous shifts. |

|

The "Sab Theek Hai" Handover |

The verbal assurance of "All is well" masked the critical reality that a primary safety barrier was disabled, leaving the incoming shift blind to the true risk. |

|

Erosion of Barrier Integrity |

Using the "Swiss Cheese Model," the bypassed interlock was the hole in the technical barrier. The undocumented handover actively blinded the human barrier, creating a second, aligned hole that allowed the hazard to become a catastrophe. |

This analysis reveals that the true failure at Pernis was not mechanical, but informational, highlighting a crucial lesson for anyone studying industrial operations.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The primary lesson from the Shell Pernis fire is stark: in high-hazard operations, the absence of robust, verified data is itself a catastrophic risk. A safety system that is disabled but not documented is functionally identical to having no safety system at all.

This incident perfectly illustrates the central theme of the "Butterfly Effect of Data Loss." The disaster was not caused by a single, massive error on the day of the fire, but by the loss of a small but critical piece of data—the status of a single bypass—during a routine shift change sometime earlier. This lost fact cascaded through subsequent shifts until it met the exact physical conditions it was meant to prevent.

Ultimately, safety and operational excellence depend on a culture that values data over intuition and verification over reassurance. We must build systems that demand clarity and reject ambiguity. The contrast is clear: true reliability comes not from the operator who says, "It's all good," but from the one who reports, "The pressure is deviating by 5%, and here is the trend." The first gives us a problem we can solve; the second gives us a silence that can destroy us.